This past week I have been helping friends pack to move, and the task I have been working on in particular is boxing a lot of old science fiction magazines and monthly anthologies, the earliest of which is from 1939. Through great effort, I have managed for the most part to avoid perusing things as I pack them. However, this is a genre dear to my heart, and naturally I’ve read quite a number of these authors and stories—they are a mainstay of my teenage memories of the Austin Public Library.

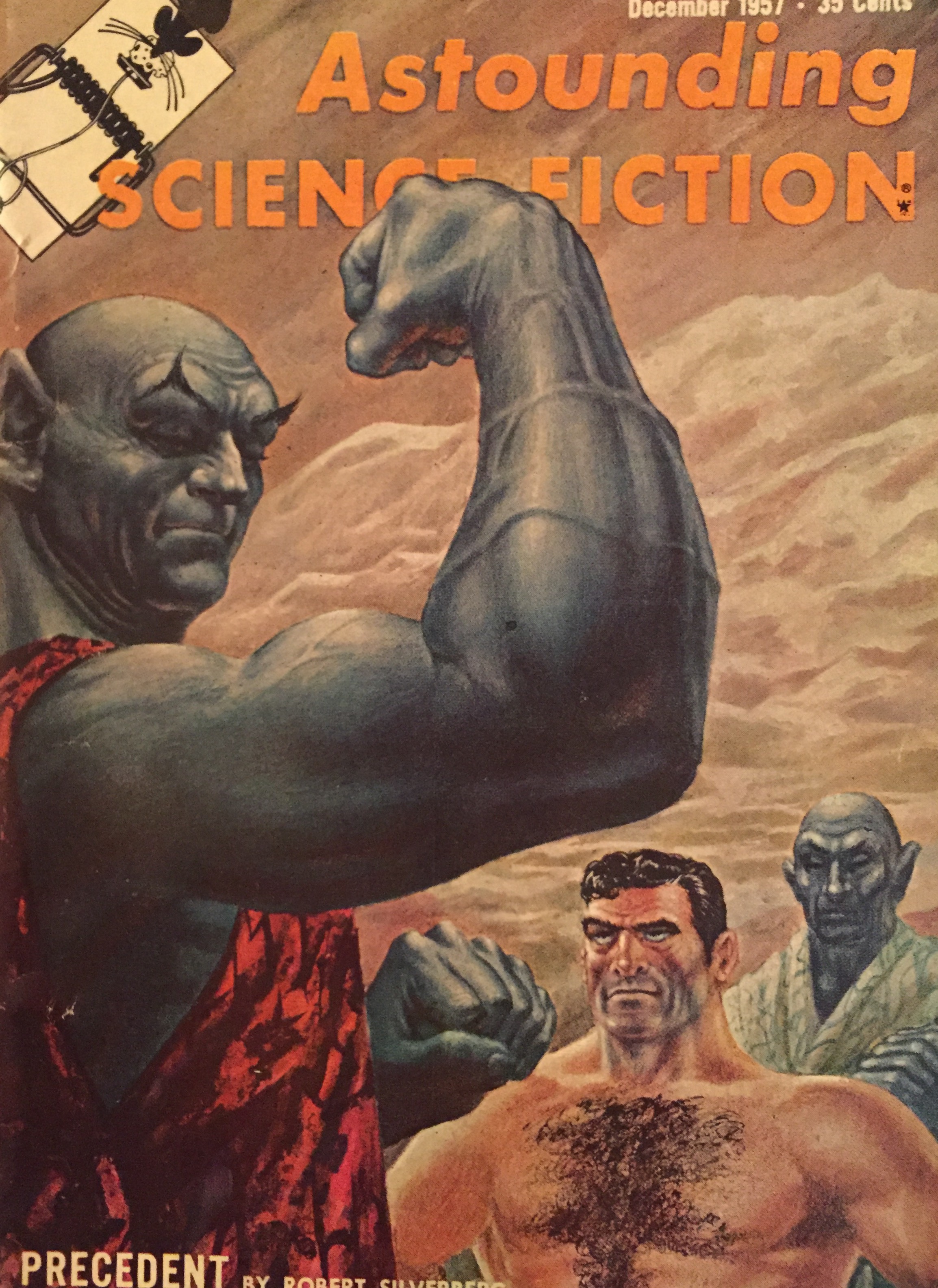

There are so many things I notice about the cover art in particular, since I don’t have to open the books to see it. The Golden Age images from the 1940s feature giant machines, stirring tales of “hard” science fiction (TL;DR… emphasis on technological problem solving and objective reasoning, comparative absence of human characteristics that don’t feed into these narrative requirements) and some assumptions that readers had at least nodding acquaintance with ballistic calculations (but not so much with human females). As actual engineering challenges started to move into space, writers started to speculate more on some of the human experiences that might go along with these new possibilities, maybe also from practical writerly concerns about being outpaced too quickly by reality; the covers start to take on some closer up pictures of men (mostly) and aliens. This partial return to the lurid writing and painting pulp styles of a generation before shaped the reading tastes of the Sad Puppies (look for your own google here) and visually set the No Girls Allowed tone familiar to readers of a certain age. Looking at it today, you can’t miss the mostly unintended homoerotic overtones and a disturbing amount of racism (unless, I suppose, you have never spent any of your life in Beast Mode). The irony is not lost on me that I am carefully preserving these images from my youth despite the fact that I cannot see myself in them except through a certain suspension of disbelief.

Nobody here looks like me.

Plenty of people better informed and more obsessive than I am have written on the history of sci-fi and gender, sci-fi and the Cold War, sci-fi and race, sci-fi and other genres, and so forth, so I will move on to the other thing I couldn’t help but notice. Several publications stated a secondary goal of keeping their readers informed on the most interesting and latest actual science and engineering. Why? Sure, Science (capital S) might well interest a lot of people—after all, it’s kind of fascinating, at least until you get into a certain depth of arcana where mere mortals cannot follow. Architecture has that same wide allure, at least until you get into hardware schedules. And of course, STEM fields are still, alas, comfortable cultural markers of masculinity, making otherwise generic YA fiction more socially acceptable for a male reader. Science makes the minivan into a nice SUV, or at least into a PT Cruiser.

However, I want to posit that the relationship between science and science fiction is roughly analogous to the relationship between Christianity and Christian fiction. I was roaming the aisles of a giant used bookstore in my previously mentioned hometown recently, and despite the carefully positioned shelves of Wicca and other edgy spiritual topics (edgier even there than they would be here, to be sure) there was a double-minivan worth of Christian Fiction. I don’t read it myself, but certainly my online students read it and talk about its greatest hits in their assignments. However, there was a time when I loved the classics by CS Lewis and Madeleine L’Engle. So I see some parallels in science fiction and science—science fiction gets readers excited about spending their careers in STEM occupations, gives them (us) concrete images of what life might look like soon (for good or for ill), and speculates on scenarios that are only beginning to come into play so that we can consider them more abstractly. Both genres, for what it’s worth, are interested in “what is it to be human” and posit some kinds of alternatives to that (demons, aliens, etc). Both genres have created memorable object lessons about who we are at our best. Both are prone to remaining overlong in the shallow water of straightforward plot pleasures. Finally, both of them also have a kind of evangelical function, pointing towards whatever they consider to be a more timeless truth (physics or God, or sometimes a mixture of those things). Sure, there are differences, but mainly, as I think of it, the two genres are kind of cousins here, cheering for their respective teams but using all the same family recipes for their TV parties.